Did We Kill the Neanderthals? New Insights Unravel an Ancient Mystery

Recent research sheds light on the complexities surrounding the extinction of Neanderthals and the potential role modern humans played in their disappearance.

Last Days of the Neanderthals

Around 37,000 years ago, small clusters of Neanderthals thrived in what is now southern Spain. Their survival faced a significant challenge following the eruption of the Phlegraean Fields in Italy, which disrupted food sources across the Mediterranean.

In their daily lives, these early humans crafted tools, foraged for food, and made artistic engravings. Despite their resourcefulness, they likely remained unaware of their impending fate.

However, the decline of Neanderthals began long before this period. Initial isolation and dispersal, starting tens of thousands of years earlier, brought an end to nearly half a million years of their existence across rugged Eurasian landscapes.

By approximately 34,000 years ago, Neanderthals had essentially disappeared. The overlapping time and space shared with modern humans resulted in speculation about whether our species directly contributed to their extinction. This influence could have stemmed from violence, disease transmission, or competition for resources.

Unraveling the Extinction Mystery

Researchers are uncovering complex factors behind the Neanderthal extinction. Shara Bailey, a biological anthropologist at New York University, emphasized that data reveals a multitude of contributors to their demise.

A combination of competition between Neanderthal groups, inbreeding, as well as interactions with modern humans, fostered their disappearance.

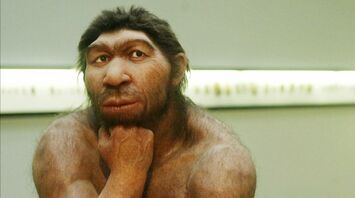

The scientific exploration of Neanderthals commenced in 1856 when quarry workers discovered a peculiar skull in Germany's Neander Valley. This skull received the classification Homo neanderthalensis. Early interpretations perceived these beings as primitive.

After over 150 years of archaeological and genetic exploration, it's now evident that Neanderthals exhibited advanced behaviors surpassing earlier assumptions. They created tools, potentially engaged in artistic expression, decorated themselves, and participated in burial practices.

Neanderthals reportedly co-existed with modern humans for a span between 2,600 to 7,000 years. Despite this overlap correlating with Neanderthal hardship, it raises questions about the impact of modern humans on their extinction.

Tom Higham, an archaeological scientist in Vienna, noted regional differences in Neanderthal demographics. Sometimes modern humans arrived in regions that had become devoid of Neanderthals, while in other areas, interbreeding occurred.

Genetic Evidence and Early Challenges

The first direct evidence of interbreeding emerged in 2010 with the sequencing of a Neanderthal genome. This research unveiled that Neanderthals and modern humans shared not only spatial territory but also genetic material.

Modern human populations, on the other hand, displayed larger sizes and greater genetic diversity, suggesting vulnerabilities within Neanderthal communities.

Omer Gokcumen, an evolutionary genomicist, emphasized the importance of genetic diversity, specifically referring to "heterozygosity." In small Neanderthal groups, inbreeding reduced genetic variation, hindering their ability to survive environmental changes and diseases.

Researchers identified a significant drop in the survival rates of Neanderthal infants, indicating that a mere 1.5% reduction in infant survivorship could spell doom for the species. As Neanderthal numbers dwindled, modern human populations flourished.

Competition with Modern Humans

Neanderthals had previously weathered significant population declines, yet they exhibited resilience. It wasn't until the pressure from modern human expansion that their population faced an ultimate threat.

Many researchers argue whether any direct violence led to the extinction of Neanderthals. Notably, a 36,000-year-old skeleton found in France bore signs of trauma, but the culprit remains uncertain. Without concrete evidence of massacres attributed to modern humans, drawing definitive conclusions remains elusive.

No genetic proof supports that diseases from modern humans eradicated Neanderthals. Nevertheless, both species share several immune-related genes, which beckon further exploration into disease's role in the extinction.

Cultural Evolution and Survival

Competition also plays a crucial role in understanding inter-species dynamics. Neanderthals demonstrated advanced cognitive skills, evident in their artifacts. However, recent findings allude to notable neurological differences between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, hinting at cognitive advantages for modern humans.

Bailey suggests that modern human concepts could proliferate efficiently within larger populations. In contrast, Neanderthal groups lacked the communal support necessary for continuous cultural evolution.

This isolation likely impaired their ability to innovate tools similarly to modern humans. While both groups experienced cultural growth around 40,000 years ago, their outcomes vary considerably.

A Multifaceted End

Numerous interactions intertwined Neanderthals and modern humans within overlapping realms. Paleoanthropologist Fred Smith proposed a hypothesis of gradual gene flow resulting in an assimilation of sorts. This theory posits that as humans advanced into Eurasia, Neanderthals ceased to exist as a defined group and became part of our lineage.

However, empirical evidence of long-term coexistence between these species remains scarce. Without qualitative archaeological evidence demonstrating sustained interactions, the degree of assimilation remains contested.

As the exploration continues, researchers note that Neanderthal extinction comprises diverse narratives. Some groups vanished; others interacted peacefully, while still more perished amid competition or violence.

Sang-Hee Lee, a biological anthropologist, underscored that the fate of Neanderthals cannot be summed under a single theory. They did not share a unified demise; rather, their extinction encapsulates a labyrinth of experiences and challenges.

Earlier, SSP reported that scientists discover a fascinating third state of life beyond death.