New DNA findings shed light on Tsavo's infamous man-eating lions

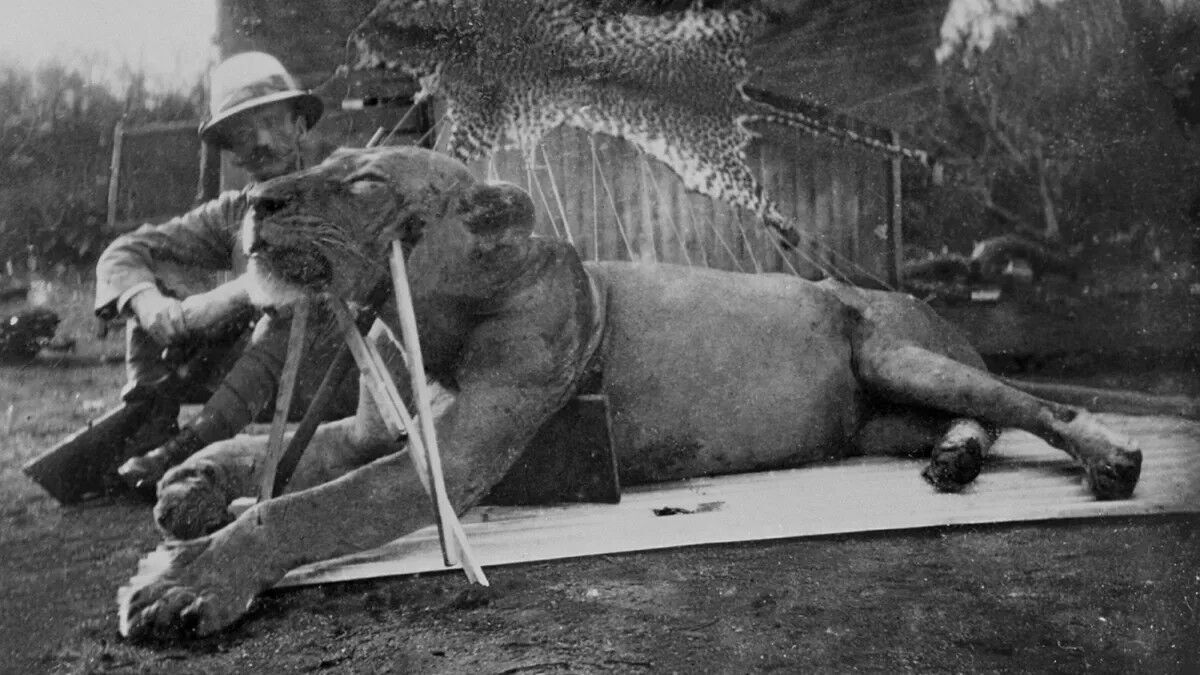

Recent DNA analyses have provided new insights into the notorious man-eating lions of Tsavo by revealing details about their diet at the time. In 1898, two male lions terrorized and killed at least 35 railway bridge workers along the Tsavo River in Kenya over a span of nine months before being killed. Their bodies are now housed at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. A new study involved extracting DNA from hair embedded in the lions' teeth, identifying six types of prey—giraffes, humans, oryx, waterbuck, wildebeest, and zebras—present during the lions' lives, and finding their own hair in the mix. This study has sparked curiosity about these lions' range and movements within Kenya.

Particularly interesting was the detection of wildebeest hair, suggesting the lions might have traveled as far as 56 miles (90 kilometers) or that wildebeest lived closer to Tsavo at the time. The lions frequented a campsite extending over 8 miles (13 kilometers) in Tsavo National Park, east of Mount Kilimanjaro. The range of these apex predators varies, from 20 to 400 square miles, dictated by prey and water availability.

Notably absent was buffalo DNA, an unexpected finding since buffaloes are an important prey species in Tsavo. Earlier research had identified buffalo presence, but the current study proposes the buffalo disappearance might relate to the rinderpest plague that decimated both buffaloes and cattle, shaping the lions' diet. Scientists have long debated the root of these lions' preference for human prey, with potential causes suggesting this dietary change may correlate with disruptions in existing prey populations due to disease or align with pain-driven complications from dental issues limiting their ability to hunt larger traditional prey. These hypotheses emerged alongside a stable isotope analysis indicating that out of as many as 135 reported human kills, around 35 composed about one-third of the diet for one lion and 13% for the other, a compelling change during their terrorizing reign.

The DNA work led by biologist Alida de Flamingh illustrates a timeline that captures the lions' evolving dietary pattern towards human predation, building on further research for clarity on how and why humans became their targets so prominently. The researchers continue to trace the historical shifts in the prey landscape and lion behavior to ultimately demystify the infamous man-eater legend.

Earlier, SSP wrote that a man developed 'headspin hole' after decades of breakdancing.